As we

reported last week, 2,700 of the world's biggest brains descended

upon New York City from January 31 to February 4, 2002, for the

World Economic Forum. Similar events in Seattle and Genoa had drawn

violent protests; in the post 9.11 New York City, such a prospect

was met with trepidation. Perhaps responding to this, the WEF made

it clear in its media releases that it proposed

to bring into discussion issues, such as workers' rights

and the environment, that are of concern to activist groups. Bill

Gates, the Corporate Motherfucker poster-boy himself, was quoted

as saying: "People who feel the world is tilted against them

will spawn the kind of hatred that is very dangerous for all of

us. I think it's a healthy sign that there are demonstrators in

the streets. They are raising the question of 'is the rich world

giving back enough?' "

For

the 7,000 protestors who showed up, however, the answer was "no."

Staging loud, yet, for the most part, non-violent protests, activists

representing a bewildering variety of causes rallied in the streets

outside the Waldorf-Astoria hotel where the forum was being held.

The New York Police Department kept a watchful eye on the proceedings,

channeling the dissenters into clearly delineated areas and diverting

traffic around the hotel.

For

the 7,000 protestors who showed up, however, the answer was "no."

Staging loud, yet, for the most part, non-violent protests, activists

representing a bewildering variety of causes rallied in the streets

outside the Waldorf-Astoria hotel where the forum was being held.

The New York Police Department kept a watchful eye on the proceedings,

channeling the dissenters into clearly delineated areas and diverting

traffic around the hotel.

Since

dissent against The Man is the theme of this Web 'zine, it was,

of course, imperative that we cover the event. The anti-globalization

movement has attracted much media attention. However, mainstream

sources have often presented the situation in the black-and-white

of a medieval mystery play, often giving undue, sensationalistic

attention to the radical anarchists who vandalize Starbucks and

McDonalds. Such portrayals simply didn't ring true. We wished to

present the event in as a non-biased a manner as possible, presenting

opinions and statements from both the protestor-on-the-street (instead

of the "leaders" usually quoted by the press) and police.

Our reasons for eschewing speaking to the organizers were several.

First of all, we weren't sure how much what they said represented

the feelings of the whole. Furthermore, speaking to a few people

with an agenda can be misleading. This was supposed to be a popular

movement; we wanted to speak to the people.

So that

we can present images along with the text, I recruited my friend

Bea,

who, besides being beautiful is an extremely talented photographer

(that's a picture of her on the right, taken with my crappy disposable

camera). All pictures on these pages, except where noted, were taken

by Bea.

We

arrived at 50th and Park Avenue at 10:00 a.m. on a freezing cold

morning to find the streets empty, save for barricades and police.

Undaunted, we began to conduct a reconnaissance, checking where

the protests would be and taking pictures of the security set-up.

The public space was sectioned off very clearly, with police politely,

yet firmly, asking passers-by for identification to enter restricted

areas. This caused no end of trouble for the various residents,

delivery people, and housecleaners going about their business. The

large, modern office buildings were likewise closed off with steel

barricades across their entrances. Locked down tight, this urban

canyon of concerete and steel presented only bare glass and stone

facades, giving the street a profoundly claustrophobic feel. And,

everywhere you looked, there were cops.

We

arrived at 50th and Park Avenue at 10:00 a.m. on a freezing cold

morning to find the streets empty, save for barricades and police.

Undaunted, we began to conduct a reconnaissance, checking where

the protests would be and taking pictures of the security set-up.

The public space was sectioned off very clearly, with police politely,

yet firmly, asking passers-by for identification to enter restricted

areas. This caused no end of trouble for the various residents,

delivery people, and housecleaners going about their business. The

large, modern office buildings were likewise closed off with steel

barricades across their entrances. Locked down tight, this urban

canyon of concerete and steel presented only bare glass and stone

facades, giving the street a profoundly claustrophobic feel. And,

everywhere you looked, there were cops.

With

no protestors to speak to, we decided to interview the omnipresent

police. The officers at the barricades were unwilling or unable

to talk, but others were more forthcoming. One NYPD officer, who

asked to remain anonymous, reveled that he had no enmity for the

protestors. In fact, we found quite a bit of common ground: We're

both descended from union organizers, who were the radicals of their

day. Nor did he seem to have any prejudiced views of the progressive

community himself; when asked what he expected of the protestors,

the officer gave a reply and resident of the Big Apple might have

voiced: "They're all probably spoiled suburban college students

from the Midwest. New Yorkers have better sense."

With

no protestors to speak to, we decided to interview the omnipresent

police. The officers at the barricades were unwilling or unable

to talk, but others were more forthcoming. One NYPD officer, who

asked to remain anonymous, reveled that he had no enmity for the

protestors. In fact, we found quite a bit of common ground: We're

both descended from union organizers, who were the radicals of their

day. Nor did he seem to have any prejudiced views of the progressive

community himself; when asked what he expected of the protestors,

the officer gave a reply and resident of the Big Apple might have

voiced: "They're all probably spoiled suburban college students

from the Midwest. New Yorkers have better sense."

In the

meantime, a more pressing issue than global capitalism had reared

its head: I had to go to the bathroom. Badly. Standing in the gusts

of freezing wind, the situation was growing desperate. Did I go

against my principles by venturing into a nearby Starbuck's? Would

that not brand me a traitor to the very people we had come to observe?

Was my bladder not about to explode?

In the

meantime, a more pressing issue than global capitalism had reared

its head: I had to go to the bathroom. Badly. Standing in the gusts

of freezing wind, the situation was growing desperate. Did I go

against my principles by venturing into a nearby Starbuck's? Would

that not brand me a traitor to the very people we had come to observe?

Was my bladder not about to explode?

Cautiously,

we ventured into the belly of the beast itself. The coffee shop

was deserted, save for some police protecting the place from any

anarchists who might have wanted to start their morning by smashing

a cappuccino machine. The cops gave us a curious once-over as Bea

documented my radical act of unlocking the bathroom door, and then

went back to drinking their lattes. Alas, I didn't perform a single

act of resistance; I even flushed and washed my hands. However,

I did discover that big, soulless businesses are good for one thing:

relieving oneself in the middle of Manhattan. You can't beat them

for convenience.

Some

police helpfully told us that the demonstrators were supposed to

march from Columbus Circle to the Waldorf, so we started walking

north and west in hopes of finding some more profitable way of amusing

ourselves than pissing on corporate property. We hadn't gone two

blocks when we ran into three young men sporting the Guatemalan

parkas, unshaven growths of beards, and matted dreadlocks that identify

dedicated counterculturalists. One carried a sticker-festooned empty

Poland Spring water jug. We introduced ourselves and asked them

who they were and what they were doing here. The three gentlemen

were hesitant to answer at first, but the one with the jug, who

asked to be identified only as Grinning White Bozo, was eventually

coaxed into responding.

"I

was hoping to have a little fun, get people dancing in the streets,"

he said. "I'm a pacifist, so I try to go with the vibes."

I pointed

to the water jug.

"Are

you soliciting donations?" I asked.

"No,

it's a drum," G.W.B. said.

"Oh,"

I replied.

Upon

further questioning, it turned out that G.W.B. and his friends had

caught a ride in from Boston with Food Not Bombs. Being from out

of town, they were rather confused as to which direction the protests

were. We told them that we were headed to Columbus Circle, and,

like the helpful New Yorkers we are, offered to show them the way.

"Don't

jaywalk!" G.W.B. cried out as we were about to cross 51st street.

I looked

at him strangely. Don't jaywalk? In New York?

"They

stopped us for jaywalking," he said. "Like, twice."

It

turned out that the police had searched the three and their bags,

and confiscated G.W.B.'s drumsticks, using jaywalking as their probable

cause. No doubt, the NYPD was searching for marijuana, and were

probably disappointed to come up empty-handed. Even without weed,

though, the three were still somewhat paranoid. They eyeballed some

nearby cops somewhat nervously while Bea photographed them standing

outside a Gap.

It

turned out that the police had searched the three and their bags,

and confiscated G.W.B.'s drumsticks, using jaywalking as their probable

cause. No doubt, the NYPD was searching for marijuana, and were

probably disappointed to come up empty-handed. Even without weed,

though, the three were still somewhat paranoid. They eyeballed some

nearby cops somewhat nervously while Bea photographed them standing

outside a Gap.

"So,

all this activism and stuff—does it impress the chicks?"

I asked.

"I

don't know, does it?" G.W.B. turned to Bea.

"I'm

not so comfortable with these guys," Bea said to me sotto

voce.

"We

should ditch them," I agreed. To them, I said, "Listen,

we shouldn't travel in a large group. You guys take that side of

the street, we'll take this side."

"Good

idea," he agreed.

Walking

down Lexington, Bea and I heard an amplified voice echoing off the

skyscrapers. We were heading towards the noise when a voice came

out of a group of cops huddled away from the wind in the arcade

of an office building.

"Where

is your jacket, young protestor?" called out a petite policewoman,

who asked us to refer to her as "Officer Smith."

"I'm

not cold," I said through chattering teeth. "And I'm not

a protestor, either. I do a Web site, and I'm writing about the

demonstration. Have any thoughts?"

"Yeah,

let them move to Afghanistan and see how they like it there,"

Officer Smith said.

I had

to admit she had a point.

Talking

to the police around the demonstration, in fact, was an interesting

experience. Once they realized I wasn't out to slander them, they

were quick to open up. And, by listening, I think I gained a better

understanding of the dynamics of what was going on.

The NYPD,

in many ways, are more legitimate working class heroes than the

college kids who had come from out of town to yell their heads off

about globalization. They were blue-collar men and women, just trying

to do their jobs and stay warm. They didn't want to hurt anyone,

and for the most part they supported the right to protest, and thought

freedom of speech was a worthwhile thing to protect. After all,

the police strongly believe in the right to unionize. On the other

hand, they didn't want anyone to hurt the city, either. Enough had

happened on September 11.

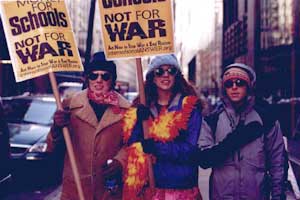

We

thanked "Officer Smith" and her colleagues and moved on.

Around the corner, we found more of what we had been looking for:

sign-carrying protestors straggling in from the west side, being

directed by the police into areas clearly marked off with steel

barriers. We took the opportunity to stop a group of three colorfully

dressed, college-age women carrying "Money for Schools, Not

War" signs. Again, they were not local, but had come down from

Boston expressly for the demonstration.

We

thanked "Officer Smith" and her colleagues and moved on.

Around the corner, we found more of what we had been looking for:

sign-carrying protestors straggling in from the west side, being

directed by the police into areas clearly marked off with steel

barriers. We took the opportunity to stop a group of three colorfully

dressed, college-age women carrying "Money for Schools, Not

War" signs. Again, they were not local, but had come down from

Boston expressly for the demonstration.

"I

think it's a bunch of bullshit that rich people are trying to make

money off the backs of poor people," said one. "The real

suffering takes place in other countries. My solution would be a

more equitable economic system. If everyone got paid the same for

the same time working, you wouldn't have such an accumulation of

wealth in the hands of the elites. But of course, the money goes

into the hands of the investors."

We

thanked the girls and pressed on Park Avenue, where we found the

purpose of the barricades we had noticed earlier. They were set

up along the street, controlling the flow of traffic. Anyone who

wanted to protest had to step, under the watchful eye of the NYPD,

behind the barricades and into a cattle-pen like area. The barriers

effectively controlled the public space, keeping the demonstrators

crammed onto the sidewalks, able to see their compatriots on the

opposite corner, but unable to join them unless they were willing

to walk all the way down the block to cross the street. (The Village

Voice reported what happened when people tried to cross

some barriers, together with some pictures calculated for maximum

shock effect.)

We

thanked the girls and pressed on Park Avenue, where we found the

purpose of the barricades we had noticed earlier. They were set

up along the street, controlling the flow of traffic. Anyone who

wanted to protest had to step, under the watchful eye of the NYPD,

behind the barricades and into a cattle-pen like area. The barriers

effectively controlled the public space, keeping the demonstrators

crammed onto the sidewalks, able to see their compatriots on the

opposite corner, but unable to join them unless they were willing

to walk all the way down the block to cross the street. (The Village

Voice reported what happened when people tried to cross

some barriers, together with some pictures calculated for maximum

shock effect.)

Being

physically separated, however, didn't seem to dampen the enthusiasm

of the groups of protestors, who, despite the freezing weather,

waved their homemade signs and enthusiastically chanted slogans

such as, "Hey, Ho, WEF has got to go!" and "Bush,

Sharon, you can't hide! We charge you with genocide!" The anonymous

police officer we had spoken to earlier was vindicated when someone

took a microphone and, in a Tom-Morello-from Rage-Against-the-Machine-like

voice shouted: "Hey, how many of us are from New York?"

A smattering

of cheers.

"How

many from out of town?"

Thunderous

applause. Pandemonium.

"Uh-how

many of us from NEW JERSEY?!"

Dead

silence.

"New

England?"

The crowd

voiced a collective "Yeah!"

The first

speaker finished, a woman identified as Stephanie from The Women's

Fight Back Network from Simmons College in Boston took the microphone.

"People

are not just losing jobs in Boston," she said. "It's happening

in every city. . . it's caused by the same thing. . . I want to

remind people that it would cost 17 billion to give health care

to every child in America, but it costs 40 billion for this war.

. ."

For

a speaker from what seemed to be a feminist group to speak out against

the war in Afghanistan fit with the theme of the event. The demonstrators

carried signs espousing a whole rainbow coalition of left-wing causes,

from environmentalists to socialists to what were apparently both

members of that well-known resistance group Queers Against the Israeli

Occupation of Palestine. (Interesting that they were interested

in the cause of people who would stone them for violating Islamic

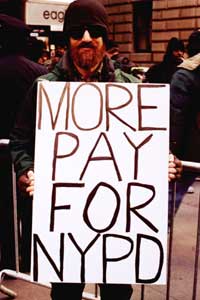

law.) One fellow, who earned high scores from the cops and Beatrice

and myself as well, even carried a "More Pay for NYPD"

sign.

For

a speaker from what seemed to be a feminist group to speak out against

the war in Afghanistan fit with the theme of the event. The demonstrators

carried signs espousing a whole rainbow coalition of left-wing causes,

from environmentalists to socialists to what were apparently both

members of that well-known resistance group Queers Against the Israeli

Occupation of Palestine. (Interesting that they were interested

in the cause of people who would stone them for violating Islamic

law.) One fellow, who earned high scores from the cops and Beatrice

and myself as well, even carried a "More Pay for NYPD"

sign.

Searching

through the mob, we finally found some New Yorkers, high school

students from LaGuardia and Brooklyn Tech. Asked why they had come

out today, one ventured: "The people should have a say in the

decision making [instead of the corporate executives]." Another

added, "All these people are warmongering and they support

Bush in his self-important war."

Alan

from Queens, who was handing out literature for the Socialist Alternative,

gave his opinion of the WEF attendees: "I think they're a bunch

of scumsuckers. They're pigs. [The WEF] is a strategic tool of international

capitalism."

"Real"

reporters, given free access to the proceedings by their press passes,

were interviewing the more colorful demonstrators over the barriers.

I saw one guy from Minnesota, his yellow raincoat decorated with

political stickers, interviewed by a French TV crew. Like so many

of the protestors we had spoken to ourselves, he gave a long, rambling

speech about nothing in particular, about how bad globalization

is. I felt bad for the French reporter trying to get quality material

out of this crowd. He were looking for a José

Bové, the dairy farmer whose crusade for quality

farm products in the face of crappy, mass-produced convenience food

made him a French national celebrity. He wanted someone to say something

concrete, like "Yes, I am protesting these people because my

uncle lost his job when his factory was moved to the Philippines,

where they pay kids two cents an hour to do his job," or "I

am protesting this Forum because my phone service works like shit,

but we can't get anything done because our Congressman sucks the

phone company's dick for his campaign money." Instead, he got

some half-baked conspiracy theory about Israel, Enron, George W.

Bush, and the Gnomes of Zurich. What was happening in that hotel

down the block, in the minds of the crowds, was all the world's

evils lumped together in one building-and they were going to root

it out, consequences be damned.

"Real"

reporters, given free access to the proceedings by their press passes,

were interviewing the more colorful demonstrators over the barriers.

I saw one guy from Minnesota, his yellow raincoat decorated with

political stickers, interviewed by a French TV crew. Like so many

of the protestors we had spoken to ourselves, he gave a long, rambling

speech about nothing in particular, about how bad globalization

is. I felt bad for the French reporter trying to get quality material

out of this crowd. He were looking for a José

Bové, the dairy farmer whose crusade for quality

farm products in the face of crappy, mass-produced convenience food

made him a French national celebrity. He wanted someone to say something

concrete, like "Yes, I am protesting these people because my

uncle lost his job when his factory was moved to the Philippines,

where they pay kids two cents an hour to do his job," or "I

am protesting this Forum because my phone service works like shit,

but we can't get anything done because our Congressman sucks the

phone company's dick for his campaign money." Instead, he got

some half-baked conspiracy theory about Israel, Enron, George W.

Bush, and the Gnomes of Zurich. What was happening in that hotel

down the block, in the minds of the crowds, was all the world's

evils lumped together in one building-and they were going to root

it out, consequences be damned.

Bea

and I had it when the crowd started shouting about the Palestinian

homeland and Israeli imperialism. Bea grew up in Germany, but her

father is Jewish and she has cousins in Israel. I've never been

to Israel, but I'm both Jewish and know people who have served in

the Israeli Defense Forces. The knee-jerk reaction of the crowd,

as well as the apparent inability of anyone who fancies themselves

a liberal to see more than one side of an issue, really bothered

us.

Bea

and I had it when the crowd started shouting about the Palestinian

homeland and Israeli imperialism. Bea grew up in Germany, but her

father is Jewish and she has cousins in Israel. I've never been

to Israel, but I'm both Jewish and know people who have served in

the Israeli Defense Forces. The knee-jerk reaction of the crowd,

as well as the apparent inability of anyone who fancies themselves

a liberal to see more than one side of an issue, really bothered

us.

"That

does it, dude, we're out of here," Bea said. "Besides,

I'm freezing. Come on, I think there was a Body Shop back there."

I couldn't

argue: the cold wind whipping between the buildings had dried and

chapped our skin, and my knuckles were so swollen I could barely

write. I had to warm up, at least for a few minutes.

We retreated

back up the block to Lexington and stole away from the crowd agitating

for social change by ducking into the warm womb of the Body Shop.

It was as though we'd entered some consumer Paradise. The sweet

odor of incense swept over me, and the New-Agey music they were

playing over the PA lulled away the tension of the mob scene outside.

Nor could any of the protestors outside have found any fault with

the least thing they sold there; it was a retail establishment conceived

in the Garden of Eden. It was everyone's liberal ideas made flesh.

On the wall was a plaque with the store's business principles—nothing

they sold was tested on animals, there were no polluting byproducts

from anything's manufacturing process, and everything was all-natural.

Looking around, I saw shelf upon shelf of tubes and jars of environmentally

correct beauty products, all made from renewable resources grown

by indigenous peoples from third-world countries.

I couldn't

afford any of it.

Bea

seized a sample jar of moisturizer and began salving her chapped

lips. I picked a small jar of green goo that cost roughly the same

as my monthly bill from my Web host. "Wow. This is made from

hemp?"

Bea

seized a sample jar of moisturizer and began salving her chapped

lips. I picked a small jar of green goo that cost roughly the same

as my monthly bill from my Web host. "Wow. This is made from

hemp?"

"Yeah,

it's great shit. Here, try this stuff," she sprayed me with

an atomizer.

"Orange,"

I said, wiping the stuff out of my eyes. "I'm probably the

best-smelling person at this protest."

(By the

way, I took the picture of Bea on the left. I deserve major props

for my mad Photoshop skillz for adjusting it until you can actually

see it's her and not, say, Lowtax in a Chewbacca costume.)

On

our way back to the subway, we passed some college students handing

out socialist newspapers. They looked so earnest, I couldn't resist

asking The Question once again:

On

our way back to the subway, we passed some college students handing

out socialist newspapers. They looked so earnest, I couldn't resist

asking The Question once again:

"So,

does left-wing politics get you chicks?"

They

looked at each other.

"Not

unless you have a tattoo of Marx on your butt," one responded

sadly.

Just

then, some protestors passed by, carrying signs and chanting, "The

People united will never be defeated."

"It's

'never be divided,' you idiots," I muttered under my

breath.

I was

disappointed. The WTF protests were not what I had expected. I went

in expecting clear-cut right and wrong, easily articulated reasons

for why globalization is bad and what we have to do to make the

world better. I thought I would find the stereotypes I'd read about:

brutal police, Gandhi-esque protestors, a battle between the Rebel

Alliance and the Evil Empire. Good against Evil. Instead, I found

people: stupid and falliable, sometimes heroic, but just people.

And, I came to realize, the people inside the Waldorf-Astoria were

just that, as well: people. Some want to do right. Some are too

stupid or lazy to care. And some just want to think of new ways

to make a buck.

I realized

something else, as well: If you're going to stand for a cause, you

ought to be able to articulate what exactly you stand for. Political

decisions should be reasoned, not taken because you're afraid not

to accept the empty rhetoric, or, worse, because you're transfering

your suburban resentment for Mommy and Daddy onto some shadowy authority

figures.

As for

me, I know where my politics lie.

Feedback?

E-mail editor@corporatemofo.com

Posted

February 3, 2002 1:46 AM

Posted

by: Freeman

at February 26, 2008 4:28 PM